Translate this page into:

Vitamin B12 deficiency masks true glycemic status: HbA1c misclassification in pre-diabetic patients

*Corresponding author: Rahul Garg, Department of Medicine, F. H. Medical College, Agra, Uttar Pradesh, India. gargrahul27@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Garg R, Thakre A. Vitamin B12 deficiency masks true glycemic status: HbA1c misclassification in pre-diabetic patients. Glob J Health Sci Res. doi: 10.25259/GJHSR_63_2024

Abstract

Objectives

To examine the relationship between vitamin B12 deficiency-induced megaloblastic anemia and HbA1c measurements, evaluate changes in HbA1c levels following B12 supplementation, investigate potential glycemic status misclassification, and assess correlations between hematological improvements and HbA1c changes over a 6-month period.

Material and Methods

This prospective interventional study conducted at a tertiary care center enrolled 383 adults (aged 18–60 years) with confirmed vitamin B12 deficiency (<200 pg/mL) and megaloblastic anemia. Participants received intramuscular vitamin B12 supplementation (1000 µg) daily for 7 days, weekly for 4 weeks, followed by monthly maintenance doses. HbA1c levels, complete blood count, and serum B12 levels were measured at baseline, 3 months, and 6 months post-intervention.

Results

Of 383 participants (58% females, mean age 42.3 ± 11.2 years), 366 completed the study. Mean HbA1c decreased significantly from 5.97 ± 0.3% at baseline to 5.6 ± 0.2% at 3 months and 5.4 ± 0.2% at 6 months (P < 0.001). Among 148 initially pre-diabetic patients (38.6%), 133 (90.1%) were reclassified as non-diabetic after treatment. Hemoglobin levels increased from 9.2 ± 1.1 to 12.8 ± 0.9 g/dL (P < 0.001), and serum B12 levels rose from 156.4 ± 32.8 to 648.5 ± 156.7 pg/mL (P < 0.001). Clinical symptoms improved in 94% of participants, with complete resolution in 82%.

Conclusion

Vitamin B12 deficiency-induced megaloblastic anemia can artificially elevate HbA1c levels, leading to significant misclassification of glycemic status. Vitamin B12 status should be evaluated before diagnosing prediabetes based on HbA1c, particularly in populations with high vitamin B12 deficiency prevalence. Current diagnostic thresholds for prediabetes may need reassessment in patients with vitamin B12 deficiency.

Keywords

Hemoglobin A1c

Pre-diabetes

Megaloblastic anemia

Vitamin B12 deficiency

INTRODUCTION

Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) is widely used as a diagnostic marker for diabetes mellitus and as an indicator of glycemic control.[1] However, various factors can affect HbA1c measurements independent of blood glucose levels such as hemolytic anemias, hemoglobinopathies, acute and chronic blood loss, pregnancy, and uremia.[2,3] Recent studies have suggested that nutritional anemias, including vitamin B12 deficiency, may influence HbA1c levels, potentially leading to misclassification of glycemic status.[4]

The relationship between anemia and HbA1c has been extensively studied, with various forms of anemia showing different effects on HbA1c measurements.[4-7] Particularly noteworthy is the impact of vitamin B12 deficiency, which affects approximately 47% of the north Indian population.[8] The resulting megaloblastic anemia is characterized by decreased red blood cell production and altered erythrocyte survival, which may theoretically impact the glycation of hemoglobin.[9,10]

Previous research has demonstrated that iron deficiency anemia can affect HbA1c levels,[11,12] but fewer studies have examined the impact of vitamin B12 deficiency-induced megaloblastic anemia on HbA1c measurements.[4,13] Understanding this relationship is crucial for accurate interpretation of HbA1c results in clinical practice, especially in populations with a high prevalence of vitamin B12 deficiency.

Aims and objectives

The study sought to:

Examine the relationship between vitamin B12 deficiency-induced megaloblastic anemia and HbA1c measurements

Determine if vitamin B12 supplementation leads to changes in HbA1c levels in these patients

Investigate whether vitamin B12 deficiency could cause misclassification of glycemic status, particularly in pre-diabetic patients

Monitor how HbA1c levels change over a 6-month period following vitamin B12 supplementation

Assess the correlation between improvements in hematological parameters and changes in HbA1c levels.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Study design and participants

We conducted a prospective interventional study at a tertiary care hospital between December 2023 and November 2024. The study enrolled 383 adults aged 18–60 years with confirmed vitamin B12 deficiency (serum B12 <200 pg/mL) and megaloblastic anemia. Unlike previous studies, we included both non-diabetic and pre-diabetic individuals (HbA1c 5.7–6.4%). Exclusion criteria included megaloblastic anemia with normal vitamin B12 levels, diabetes, other causes of anemia, uremia, use of medications affecting HbA1c, and pregnancy or lactation.

Intervention

Participants received intramuscular vitamin B12 (1000 µg) once daily for 7 days, followed by weekly injections for 4 weeks, and then monthly maintenance doses for the remainder of the 6-month study period. Treatment adherence was monitored through clinic visits and injection records.

Data collection

We collected baseline demographic data, complete blood count, serum vitamin B12 levels, fasting plasma glucose, and HbA1c measurements. Follow-up assessments of hematological parameters and HbA1c were performed at 3 and 6 months post-intervention. Clinical symptoms were evaluated using a standardized questionnaire based on validated tools from various studies. The questionnaire evaluated the following: (a) Neurological symptoms such as peripheral neuropathy, balance problems, cognitive changes, and mood alterations, (b) Hematological symptoms such as fatigue, shortness of breath, and exercise intolerance, and (c) Gastrointestinal symptoms such as appetite changes, gastrointestinal discomfort, and glossitis. Modified Fatigue Impact Scale, a validated 21-item questionnaire, was used to assess physical, cognitive, and psychosocial functioning, Toronto Clinical Scoring System was used for neuropathy assessment, and visual analog scale was used for key B12 deficiency symptoms such as glossitis, appetite changes, shortness of breath, and exercise tolerance. The questionnaires were administered by trained clinicians at baseline, 3 months, and 6 months. All administrators underwent standardized training in questionnaire administration to ensure consistency. The instruments were translated into local languages following World Health Organization translation-back translation guidelines. Composite symptom scores were calculated according to each instrument’s validated scoring system.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was conducted using statistical package for the social sciences version 26.0. We performed paired t-tests for comparing continuous variables before and after intervention, Chi-square tests for categorical variables, repeated measures analysis of variance for analyzing changes over multiple time points, and multivariate linear regression to control for potential confounders including age, gender, body mass index, baseline nutritional status (using serum albumin and pre-albumin), dietary patterns (vegetarian vs. non-vegetarian), and socioeconomic status. Subgroup analyses were conducted based on age groups (18–30, 31–45, and 46–60 years), gender, baseline B12 levels (<100, 100–150, 151–200 pg/mL), baseline hemoglobin levels, and nutritional status.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics

Of 383 enrolled participants, 366 (95.7%) completed the study. The mean age was 42.3 ± 11.2 years, with 58% female participants. Mean baseline measurements included: Hemoglobin 9.2 ± 1.1 g/dL, serum vitamin B12 156.4 ± 32.8 pg/mL, fasting glucose 92.3 ± 4.8 mg/dL, and HbA1c 5.97 ± 0.3% [Table 1].

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Total participants | 383 |

| Mean Age (years) | 42.3±11.2 |

| Females | 222 (58%) |

| Males | 161 (42%) |

| Mean Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 9.2±1.1 |

| Mean Serum B12 (pg/mL) | 156.4±32.8 |

| Mean Fasting glucose (mg/dL) | 92.3±4.8 |

| Mean HbA1c (%) | 5.97±0.3 |

HbA1c: Hemoglobin A1c

Primary outcomes

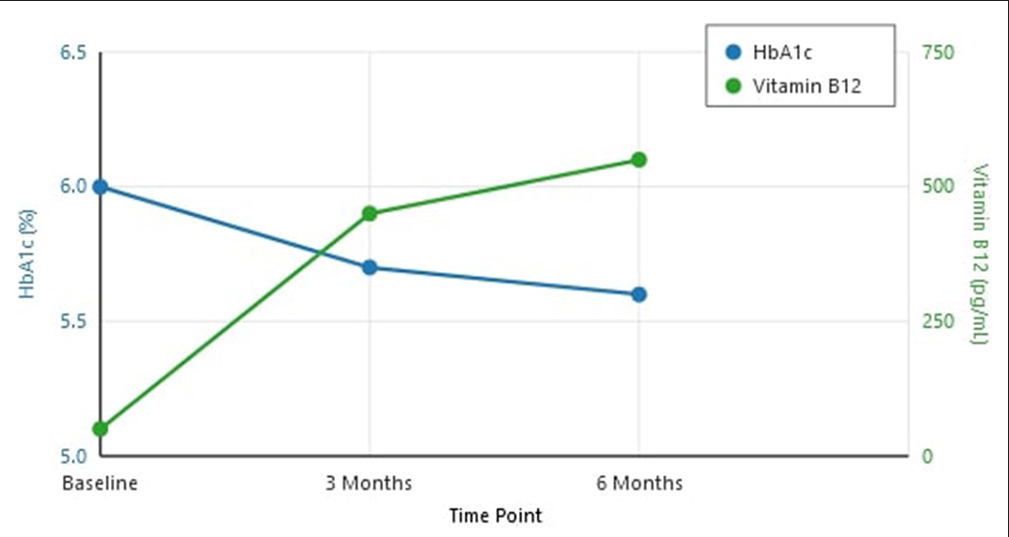

HbA1c levels showed a significant reduction following vitamin B12 supplementation [Figure 1]:

Baseline: 5.97 ± 0.3%

3 months: 5.6 ± 0.2% (P < 0.01)

6 months: 5.4 ± 0.2% (P < 0.001).

- Changes in hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) and vitamin B12 levels over 6 months.

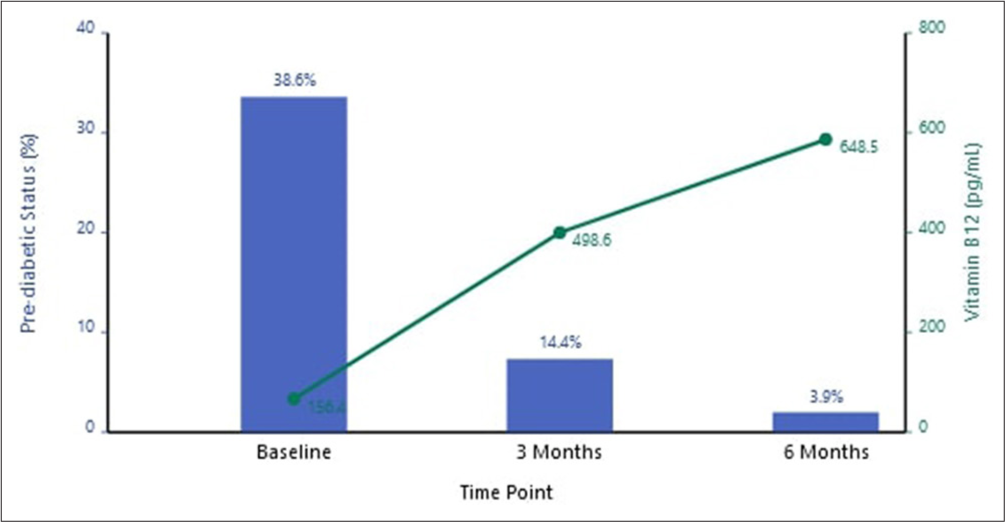

Glycemic status reclassification

At baseline, 148 participants (38.6%) were classified as pre-diabetic based on HbA1c criteria (5.7-6.4%). After vitamin B12 supplementation:

At 3 months: 93 participants (62.7% of initially pre-diabetic patients) were reclassified as non-diabetic

At 6 months: 133 participants (90.1% of initially pre-diabetic patients) were reclassified as non-diabetic [Figure 2].

- Pre-diabetic status and Vitamin B12 levels over time (Blue bars: Pre-diabetic status, Green line: Vitamin B12 levels).

Secondary outcomes

Hematological parameters improved significantly [Table 2]:

Mean hemoglobin increased from 9.2 ± 1.1 g/dL to 12.8 ± 0.9 g/dL (P < 0.001)

Mean corpuscular volume normalized in 92% of participants

Serum vitamin B12 levels increased to 648.5 ± 156.7 pg/mL

| Parameters | Baseline | 3 months | 6 months | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HbA1c (%) | 5.97±0.3 | 5.6±0.2 | 5.4±0.2 | <0.001 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 9.2±1.1 | 11.5±1.0 | 12.8±0.9 | <0.001 |

| Serum B12 (pg/mL) | 156.4±32.8 | 498.6±142.3 | 648.5±156.7 | <0.001 |

| MCV (fL) | 102.8±8.4 | 94.6±5.2 | 88.4±4.1 | <0.001 |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dL) | 92.3±4.8 | 91.8±4.5 | 91.5±4.6 | 0.42 |

| Pre-diabetic status, n(%) | 148 (38.6%) | 55 (14.4%) | 15 (3.9%) | <0.001 |

HbA1c: Hemoglobin A1c, MCV: Mean corpuscular volume

Clinical symptoms improved in 94% of participants, with complete resolution in 82%.

Subgroup analyses

Age-specific analysis revealed:

Greater HbA1c reduction in younger participants (18–30 years: 0.65 ± 0.15% vs. 46–60 years: 0.48 ± 0.12%, P = 0.003)

Faster hematological response in the 18–30 years of age group.

Gender differences showed:

Similar HbA1c reductions between males and females (0.58 ± 0.14% vs. 0.56 ± 0.13%, P = 0.42)

Slightly faster symptom improvement in females (mean time to improvement 4.2 vs. 4.8 weeks, P = 0.03).

Multivariate analysis revealed:

Baseline B12 levels independently predicted HbA1c reduction (β=−0.34, P < 0.001)

BMI significantly influenced response to treatment (β = 0.28, P = 0.02)

Dietary pattern (vegetarian vs. non-vegetarian) affected treatment response (β = 0.25, P = 0.03).

DISCUSSION

Our prospective interventional study provides compelling evidence that vitamin B12 deficiency-induced megaloblastic anemia significantly impacts HbA1c measurements, leading to potential misclassification of glycemic status in patients. The findings demonstrate substantial reductions in HbA1c levels following vitamin B12 supplementation, independent of changes in blood glucose levels, suggesting that B12 deficiency may artificially elevate HbA1c readings.

Impact on HbA1c measurements

The observed reduction in mean HbA1c from 5.97 ± 0.3% at baseline to 5.4 ± 0.2% at 6 months post-supplementation represents a clinically significant change that cannot be attributed to alterations in glucose metabolism, as evidenced by the stable fasting glucose levels throughout the study period (baseline: 92.3 ± 4.8 mg/dL; 6 months: 91.5 ± 4.6 mg/dL; P = 0.42). The magnitude of HbA1c reduction in our study (mean decrease of 0.57%) is particularly noteworthy when compared to the findings of Alzahrani et al.[5] who reported varying effects of different types of anemia on HbA1c. Our results suggest that the impact of vitamin B12 deficiency-induced megaloblastic anemia on HbA1c may be more substantial than previously recognized,[4] especially in populations with a high prevalence of B12 deficiency. Gram-Hansen et al.[13] demonstrated that there were no significant differences in HbA1c concentrations in iron-deficient patients, vitamin B12-deficient patients, and healthy controls. Katwal et al.[6] stressed on the need for screening for anemia in patients before proper estimation of HbA1c levels. A systematic review done by English et al.[14] showed that HbA1c is likely to be affected by iron deficiency with a spurious increase in HbA1c values, whereas non-iron deficiency anemia may lead to a decreased HbA1c value.

Mechanism of HbA1c elevation

The relationship between vitamin B12 deficiency and elevated HbA1c can be explained through several well-documented mechanisms as stated by Green et al.[10] and Hariz and Bhattacharya:[9] (1) Altered erythropoiesis: Vitamin B12 deficiency impairs deoxyribonucleic acid synthesis and nuclear maturation in erythroid precursors, leading to ineffective erythropoiesis. This results in prolonged erythrocyte lifespan, increased exposure time to ambient glucose, and enhanced hemoglobin glycation independent of blood glucose levels. This mechanism is similar to that observed in iron deficiency anemia, as reported by Bindayel,[11] though the underlying pathophysiology differs. Sinha et al.[12] demonstrated an elevation in HbA1c levels in patients with iron deficiency anemia with treatment, mechanism being attributed to unknown variables. (2) Membrane changes: B12 deficiency affects erythrocyte membrane stability and permeability, potentially altering glucose transport and glycation rates. (3) Oxidative stress: Vitamin B12 deficiency increases oxidative stress markers, which may accelerate protein glycation processes.

Additionally, the improvement in hematological parameters observed in our study (hemoglobin increase from 9.2 ± 1.1 to 12.8 ± 0.9 g/dL) correlates strongly with HbA1c reduction, supporting the hypothesis that altered erythrocyte dynamics directly influence HbA1c measurements. This finding is consistent with the work of Gunton and McElduff,[7] who demonstrated the impact of various hematological disorders on HbA1c accuracy.

Clinical significance of misclassification

Perhaps the most striking finding of our study is the reclassification of glycemic status in 90.1% of initially pre-diabetic patients following vitamin B12 supplementation. This has profound implications for clinical practice, particularly in regions with high prevalence of vitamin B12 deficiency. The potential for misclassification raises concerns about:

Overdiagnosis of prediabetes

The initial classification of 148 participants (38.6%) as pre-diabetic, with subsequent reclassification of 133 patients to non-diabetic status after B12 supplementation, suggests a significant risk of overdiagnosis when vitamin B12 status is not considered.

Healthcare resource allocation

Misclassification may lead to unnecessary interventions, monitoring, and healthcare expenditure for patients incorrectly identified as pre-diabetic.

Psychological impact

Incorrect diagnosis of prediabetes can cause unnecessary anxiety and lifestyle modifications in affected individuals.

Implications for clinical practice

Our findings necessitate several modifications to the current clinical practice:

-

Screening Protocols: Vitamin B12 testing should be incorporated into the diagnostic workflow before establishing prediabetes diagnosis based on HbA1c, particularly in:

Populations with high prevalence of B12 deficiency

Vegetarian individuals

Elderly patients

Patients taking metformin or proton pump inhibitors.

Diagnostic thresholds: Current HbA1c thresholds for prediabetes diagnosis (5.7–6.4%) may need reassessment in patients with vitamin B12 deficiency. This aligns with recommendations from the International HbA1c Consensus Committee[3] regarding the need for consideration of factors affecting HbA1c measurement.

Monitoring Strategy: Regular monitoring of both vitamin B12 and HbA1c levels may be necessary in patients with borderline HbA1c elevations, as suggested by Vikøren et al.[2]

Limitations of the study

Several limitations must be acknowledged when interpreting our results. The single-center design, conducted at a tertiary care facility in North India, may limit the generalizability of our findings to other populations and healthcare settings. The follow-up period of 6 months, while sufficient to demonstrate significant changes in HbA1c levels, may not capture longer-term effects or stability of these changes. A notable limitation was the absence of a control group consisting of vitamin B12-deficient patients without anemia, which could have helped differentiate the specific effects of anemia versus B12 deficiency on HbA1c measurements. Additionally, potential confounding factors such as concurrent medications may not have been fully accounted for in our analysis. The study also lacked continuous glucose monitoring, which could have provided more definitive evidence ruling out any subtle glycemic variations that might have influenced HbA1c levels.

CONCLUSION

This study provides evidence that vitamin B12 deficiency-induced megaloblastic anemia can artificially elevate HbA1c levels, leading to misclassification of glycemic status in a significant proportion of patients. The finding that 90.1% of initially pre-diabetic patients were reclassified as non-diabetic after vitamin B12 supplementation emphasizes the importance of considering vitamin B12 status when interpreting HbA1c results. These findings suggest that current diagnostic thresholds for prediabetes may need reassessment in patients with vitamin B12 deficiency, and vitamin B12 screening should be considered before establishing prediabetes diagnosis based on HbA1c alone.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the hospital staff and laboratory personnel for their assistance with this study.

Ethical approval

The research/study approved by the Institutional Review Board at FH Medical College and Hospital, Agra, number FHMC/IEC/R cell/2023/33, dated October 19, 2023.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript, and no images were manipulated using AI.

Financial support and sponsorship: Nil.

References

- Hemoglobin A1C In: StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls; 2022. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK549816/ [Last accessed on 2023 Mar 13]

- [Google Scholar]

- Sources of error when using haemoglobin A1c. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2014;134:417-21.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International HbA(1c) Consensus Committee 2010 consensus statement on the worldwide standardization of the hemoglobin A1c measurement. Clin Chem. 2010;56:1362-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Relationship between glycosylated hemoglobin and vitamin B12 deficiency anemia. North Clin Istanb. 2022;9:459-63.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The effect of different types of anemia on HbA1c levels in non-diabetics. BMC Endocr Disord. 2023;23:24.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The effect of anemia and the goal of optimal HbA1c control in diabetes and non-diabetes. Cureus. 2020;12:e8431.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hemoglobinopathies and HbA(1c) measurement. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:1197-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitamin B12 deficiency is endemic in Indian population: A perspective from North India. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2019;23:211-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Megaloblastic anemia In: StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls; 2022. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537254/ [Last accessed on 2023 Apr 03]

- [Google Scholar]

- Influence of iron deficiency anemia on glycated hemoglobin levels in non-diabetic Saudi women. J Int Med Res. 2021;49:300060521990157.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Effect of iron deficiency anemia on hemoglobin A1c levels. Ann Lab Med. 2012;32:17-22.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c) in iron-and vitamin B12 deficiency. J Intern Med. 1990;227:133-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The effect of anaemia and abnormalities of erythrocyte indices on HbA1c analysis: A systematic review. Diabetologia. 2015;58:1409-21.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]