Translate this page into:

The prevalence of depressive symptoms among frontline healthcare workers during COVID-19 pandemic: A rapid umbrella review

*Corresponding author: Dorra Parv, Department of Clinical Psychology, Iranshahr University of Medical Sciences, Iranshahr, Iran dorraparv@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Parv D. The prevalence of depressive symptoms among frontline healthcare workers during COVID-19 pandemic: A rapid umbrella review. Glob J Health Sci Res. doi: 10.25259/GJHSR_25_2024

Abstract

There is a large body of research with multiple systematic reviews on the prevalence rate of mental health conditions in healthcare workers (HCWs) during the COVID-19 pandemic. The reports on mental health conditions have been contradictory, especially on the prevalence rate of depression. The rapid umbrella approach sought to fill this research gap. The symptoms of depression had a rate of 24–36% in the HCW community, and 14– 53% in the frontline HCW population. Female HCWs, nurses, and frontline health workers showed a prevalence of a larger rate of depression. Earlier reports have been highly heterogeneous, representing a key explanation for the substantially varied reports on depression rates in HCWs and frontline HCWpopulations. Thus, it is suggested that future research, including meta-analysis and primary research works, should be focused on minimizing the inconsistency of results and maximizing their reliability using efficient and effective techniques.

Keywords

COVID-19

Depression

Frontline

Health workers

Prevalence

INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 pandemic emerged in Wuhan, China, in late 2019 and spread across the world in a short time.[1-8] It not only caused significant mortality and morbidity rates but also had dramatic health consequences, such as mental health conditions.[9-12]

The healthcare worker (HCW) population, especially frontline HCWs, would potentially have a higher vulnerability to such conditions.[13-17] The fear of COVID-19 infection, witnessing COVID-caused colleague mortality, prolonged work shifts, the unavailability of effective therapeutic strategies, social distancing, separation from family/colleagues, and the severe illness of COVID-19 patients were among the factors that could pose an adverse effect on the mental health of HCWs.[16]

There is a large body of research with multiple reviews on the rate of mental conditions in the HCW community.[15,18-22] Earlier works have reported contradictory results on the rate of depression in HCWs.[8,15,20-23] To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this study pioneers the analysis of the rate of depression in frontline HCWs on a global scale through the rapid umbrella approach.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines were adopted in this review.[24]

Search strategy

The papers were collected from various systematic review databases, including Google, Cochrane, and Google Scholar, based on the keywords of COVID-19, disorder, illness, mental, psychiatric, pandemic, coronavirus, depression, prevalence, nurse, doctor, meta-analysis, systematic review, and frontline HCW for a duration between October 6–13, 2021.

The titles and abstracts of the papers were employed for screening based on particular inclusion and exclusion criteria. Once the screening of the titles and abstracts had been completed, inclusion criteria were applied to review the full-text versions of the papers. The inclusion criteria included:

Systematic reviews

Numerical data provided on depression prevalence rates in HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic

English papers

Peer-reviewed journal publications.

Data extraction

A researcher-constructed form was employed to extract data on factors such as the first author, publication year, HCW sample size, frontline HCW sample size, depression evaluation scale, and overall HCW depression prevalence.

Quality assessment

The critical appraisal tools of the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) for systematic reviews, particularly the Checklist for Prevalence Studies, were utilized to assess the quality of the selected papers.[25]

Data synthesis

Since primary reports had significant inconsistency/ interference, data were synthesized through a narrative approach.

RESULTS

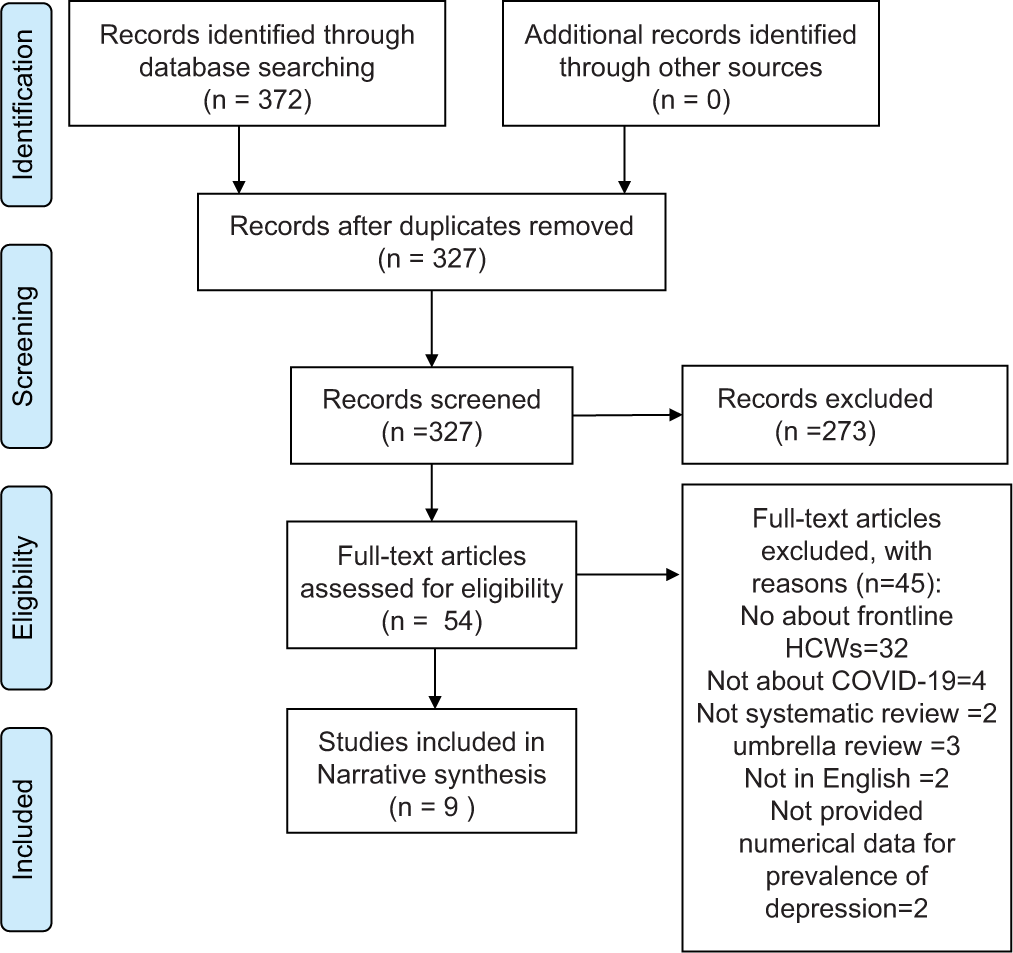

Figure 1 represents the potential papers, search and screaming procedure, and reported findings.

- PRISMA flowchart of literature search.

Characteristics of the included papers

Three of the nine meta-analyses were conducted in 2020, with the remaining six being reported in 2021. Moreover, 60% (259) of the 429 primary studies had been conducted in China, mostly using online questionnaires and adopting a cross-sectional design.

They mostly reviewed females. Several measures with various cut-offs had been used to assess depression, with the majority of the papers using patient health questionaire-9 assessment. The quality scores of six meta-analyses were found to be high based on the JBI scale, including three papers with a score of 7, two papers scoring 9, and the one remaining meta-analysis scoring 10. This umbrella review also found three of the works having medium quality scores (two with a score of 7 and one with a score of 4).

The depression prevalence heterogeneity of the included reviews was significant. The HCW community had been reported to have a depression prevalence rate of 24–53%, and the female HCWs showed higher rates of depression symptoms than their male counterparts. The frontline HCWs also showed higher depression rates than the other HCWs, and depression was more prevalent among nurses than among doctors. The rate of depression was also larger in PHQ-9 reviews than in papers using other depression scales based on subgroup analysis, as shown in Table 1.[3,7,26-31]

| First author (year) | Batra (2020)[27] | Wu et al. (2021)[31] | Salari et al. (2020)[7] | Bareeqa (2021)[29] | Al-Maqbali et al. (2021)[26] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of primary studies | 65 | 66 | 29 - among them, 21 studies had focused on depression | 19 | 93 |

| Country of primary studies | 51 from Asia (31 from China, 4 from India, 3 from Iran, 2 from Pakistan, 2 from Jordan, 1 from Bahrain, 1 from Hong Kong, 1 from Israel, 1 from Nepal, 1 from Oman, 1 from Saudi Arabia, 1 from South Korea, 1 from India and 1 from Singapore), 10 were from Europe (3 from Italy, 4 from Turkey, 1 from Switzerland, 1 from Serbia, 1 from Ireland), 2 were from south America (1 from Argentina, Brazil, Chile and Mexico, and one from Brazil alone), and 2 from North America | 62 from China, 1 each from Iran, Jordan, Singapore and India | 19 studies from China, 2 studies from Iran, 2 studies from Hong Kong, 1 study each from following countries: Singapore, Romania, India, France, Australia, and others | China | China=49 other countries=44 |

| Total sample size | 79437 | Depression data were reported by 48 studies with 125121 participants drawn from seven populations | 22380 in total and 1024 in the frontline | 62382 | 93112 |

| Numbers of HCWs | 62382 | 93112 | |||

| Numbers of frontline HCWs | 16 studies, 36315 (45/7% ) were nurses, 19287 (25%) were doctors, and the remaining were from other occupational groups | 10429 | 4 studies in nurses and 2 studies in physicians, with 8063 and 643 participants, respectively | 8 studies with 10267 frontline HCWs | NR |

| Mean age | NR | NR | NR | 36/44 | NR |

| Sex | |||||

| M | NR | 7856 | - | NR | |

| F | 57244 (72%) were female | NR | 14524 | 69/7% | NR |

| Most instruments are used for depression. | PHQ-9 | NR | SDS=7 DASS -21=7 BDI -II=4 HAD=1 | PHQ-9 | PHQ-9=10 studies SDS=2 HADS=2 DASS=4 BDI-II=1 Study PHQ-2=1 Study PHQ-4=1 study |

| Cut off point | Varied cut-off points of PHQ-9 including 4 and over (2 studies), 5 and over (6 studies), 10 and over (7 studies), and 15 and over | ||||

| (1 study) | NR | NR | NR | With varied cut-off points | |

| Pooled prevalence of depression among HCWs | 31/8% in 46 primary studies | 31/4% | |||

| (95% CI 27/3–33/5%) | 24/3% (95% | ||||

| CI: 18/2–31/6%). | 26/9% (95% CI: (20–34/3% I2=99/68%) | ||||

| Prevalence of depression among front-line HCWs | 23/6% compared to 19/6% among second line HCWs | 28/8% (20/7–37/6) Among frontline and 26/2% (18/4–34/8) among second line physician and nurses | In physicians=40/4% (95% | ||

| CI: 36/4–44/5%) in nurse=28% (95% CI: 16–44/2%) | 31/5% (95% CI; 24–43%, I2=99/30%) | 33% (95% | |||

| CI: 24–43, I2=99). | |||||

| Heterogeneity | Significant, I2=99/2% | A high degree of heterogeneity was found (I2=99/6%) | I2=98/9 | Significant, 99/68% | Significant, I2=99 |

| Method of analysis | Random effects model | Random effects model | Random effects model | Random effects model | Random effects model |

| Study design | Cross-sectional | 95/5% Were cross-sectional, and most were online surveys | NR | Cross-sectional | Cross-sectional |

| Subgroup analysis | Conducted that showed higher anxiety and depression among females, nurses, and frontline HCWs than among males, doctors, and second-line HCWs. | Conducted that showed physicians and nurses had the highest prevalence of depression, anxiety, distress, and insomnia, while nonmedical staff had the lowest prevalence | Conducted that showed that the Prevalence of depression in physicians was higher than in other hospital staff | Conducted that the prevalence of depression assessed via PHQ-9 was higher than other instruments (35/5%) and showed that the prevalence of depression was higher among frontline HCWs and women. | The study showed that the prevalence of depression in low risk of bias studies was higher (39%) than that of moderate risk of bias (34%). |

| Setting | NR | NR | Hospital | Hospital=67 studies mixed setting=17 not reported=9 | |

| First author (year) | Sun et al. (2021)[28] | Dutta et al. (2021)[29] | Olaya et al. (2021)[30] | Hao et al. (2021)[3] | |

| Total number of primary studies | 47 | 33 | 57- among them, 48 studies reported the prevalence of depression in HCWs | 20 | |

| Country of primary studies | China=29 Iran=2 Italy=2, 1 study each for Singapore, France, Ecuador, Libia, Philipines, Pakistan, Poland, Saudi Arabia, Brazil, Spain and America | 18 from China, 4 from India, 2 from Pakistan and 0ne each from Iran, Turkey, Singapore, Brazil, Italy, Poland, Jordan, Nepal, US | China=32, Italy=3 Turkey=3 India=4, Singapore=1, Kameron=1 and 1 each for Spain, Libya, Kosovo, Nepal, USA, Switzerland, Jordan, Croatia, Serbia, Poland, South Korea, Brazil, Iran | China=19 studies, Singapore=1 | |

| Total sample size | 81277 | 39703 | 53505 | 12788 | |

| Numbers of HCWs | 81277 | 35843 | 53505 | 10886 | |

| Numbers of frontline HCWs | Mostly frontline (doctors and nurses) | 21 studies with 19840 total participants, including 16003 doctors and 19840 nurses | 5704 | NR | |

| Mean age | 18-53 | NR | NR | NR | |

| Sex | |||||

| M | 30% | ||||

| F | Mostly females | 64/35% | Mostly females | 70% | |

| Most instruments are used for depression. | PHQ-9=17 HADS=5 SDS=4 PHQ-2=3 DASS=3 DASS-21=2 CES-D=2 HAMD=1 | PHQ-9=8 studies DASS-21=8 studies SDS=4 studies HADS=4 studies PHQ-4=2 studies CES -D=2 studies HDRS=1 BDI-2=1 | Mostly used PHQ-9, n=27 studies DASS-21, n=8 and HADS, n=8 studies | PHQ-9, SCL-90, PHQ-2 and SDS | |

| Cut off point | Varied cut-off points of PHQ-9, including 4, 5, and 10 and over, as well as for DASS-21, including over 9 and 10 | Varied cut of points including 10 and over, n=21 studies for PHQ-9 and 5 cut off point 5 in 4 studies and 9 and over in 1 study | Varied cut of points | ||

| Pooled prevalence of depression among HCWs | 32/4% (95% CI: 25/9–39/3, I2=99%) | 24%, nurses=25% medical doctors=24% | 24/1% (95% CI: 16/2–32/1, I2=99%) | ||

| Prevalence of depression among front-line HCWs | 28% (19/4–37/4, I2=98/8%), other healthcare workers (13/1% (3/2–27/4%, I2=97/8%) | Up to 43% | 14/6%, [95% CI: 6/3–23%, I2=91%] is higher than those in the second line 8/7%, [95% CI: 3/9–13/4%., I2=94%, P<0/01]. | ||

| Heterogeneity | High heterogeneity found (I2=98/8%) | Significant | Significant, [I2=99%, P=0/01] | ||

| Method of analysis | Random effects model | Random effects model | Random effects model | ||

| Study design | Cross-sectional | Cross-sectional (online surveys) | Cross-sectional | ||

| Subgroup analysis | Conducted that showed a higher incidence of depression among women and frontline HCWs. Also, Nurses had higher rates of depression than doctors. | Conducted that showed a higher prevalence of depression assessed by PHQ-8 (42/8%) than assessed by other instruments. | Conducted that showed that the prevalence of depression was lower in China, in studies that used convenience sampling method, and in high methodological quality studies | Conducted that shows that the prevalence of depression was significantly associated with the instrument used for assessing depression and no correlation between the prevalence of depression and sample size, hospital, position (frontline or non-frontline), and type of staff (nurses, physicians, or mixed). | |

| Setting | Mostly institutional setting | NR | Hospital-based=18, Population-based=2 |

HCW: Healthcare worker, CI: Confidence interval, NR: Not reported, PHQ: Patient health questionaire, SDS: Zong self-rating depression scale, DASS: Depression anxiety and stress scale, BDI: Beck depression inventory, HAD: Hospital anxiety and depression, HADS: Hospital anxiety and depression scale, CES-D: Center for epidemiologic studies depression rating scale, HDRS: Hamilton depression rating scale, I2: Reperesents heterogeneity or it is as an heterogeneity index.

DISCUSSION

This study used the rapid umbrella technique to tackle the inconsistency in reports on the prevalence rate of depression in frontline HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The results of this study showed that the prevalence rate of depressive symptoms among all HCWs ranged from 24% to 36%, and among frontline HCWs ranged from 14% to 53%.

A review of earlier reports demonstrated that the findings had been highly consistent, in agreement with earlier umbrella reviews on the HCW community.

A depression rate of 5–89% was reported in earlier umbrella reviews, reviews, and meta-analyses for general populations, HCWs, and frontline HCWs.[8,16,18,20,26,32-37]

The included reviews were found to be significantly heterogeneous. This heterogeneity is potentially the explanation for the substantial variation of depression rates reported for HCWs and frontline HCWs. Different methodologies, depression assessment measures, sampling techniques, cut-off points, locations, methodological shortcomings/defects, and demographics can be other explanations.[20,38]

This study found that primary studies had been conducted in a broad range of countries with various socioeconomic and cultural differences using various methodologies, e.g., different depression assessment measures with various cutoffs. This agrees with the literature.

Most of the papers had biased sampling since they did not sample participants randomly. This can be an explanation for the significant variation/inconsistency in the rates of depression prevalence. This study estimated a larger depression rate for female HCWs than for male HCWs, for nurses than for doctors, and frontline HCWs than for nonfrontline HCWs. This agrees with earlier works. Fan et al.[11] adopted an umbrella approach and found that HCWs in high-risk settings had short- and long-term mental health conditions, including post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and depression, during pandemics/epidemics.

Chigwerde et al.[39] reported a systematic review to find potential mental health risks, e.g., frontline healthcare (high-risk) settings, nurse/female, unavailability of personal protection equipment, inadequate virus knowledge, prolonged work shifts, lack of social support, experience, poor healthcare, history of quarantine, and poor/no education.

Koontalay et al.[40] analyzed the COVID-caused burden on HCWs through a qualitative systematic review. Insufficient equipment, emotional challenges, occupational burnout, and insufficient knowledge were categorized as themes with negative impacts on both the mental and physical health of frontline HCWs, ultimately causing depression, stress, anxiety, and fear.

CONCLUSION

This study adopted an umbrella review approach and found significant inconsistency in the reported rates of depression prevalence in HCWs and explained it by heterogeneity in earlier works. Nevertheless, HCWs, especially frontline HCWs, have been reported to have high prevalence rates of depressive symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic. It is recommended that preventive measures be implemented to mitigate depression in the HCW community.

Due to the significant heterogeneity/inconsistency of the reported depression rates, it is suggested that efficient and effective techniques should be coupled with the same depression assessment measures in future research to minimize errors. It is also recommended that future systematic reviews, particularly meta-analyses, review primary studies of higher homogeneity to maximize prevalence rate synthesis in various papers.

Ethical approval

Institutional Review Board approval is not required.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent is not required as there are no patients in this study.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The author confirms that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript, and no images were manipulated using AI.

Financial support and sponsorship: Nil.

References

- Global prevalence of mental health problems among healthcare workers during COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2021;121:104002.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The mental health of healthcare workers in the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2020;19:1967-78.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and risk factors of mental health problems among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:567381.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mental health outcomes among health-care workers dealing with COVID-19/severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Indian J Psychiatry. 2021;63:335-47.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2020;277:55-64.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Association between ABO blood groups and COVID-19 infection, severity and demise: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect Genet Evol. 2020;84:104485.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The prevalence of stress, anxiety, and depression within front-line healthcare workers caring for COVID-19 patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Resour Health. 2020;18:100.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anxiety and depression among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic umbrella review of the global evidence. BMJ Open. 2021;11:eo54528.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Impact of COVID-19 pandemic in public mental health: An extensive narrative review. Sustainability. 2021;13:3221.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The effects of COVID-19 on mental health and wellbeing in a representative sample of Australian adults. Front Psychiatry. 2021;11:579985.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An umbrella of the work and health impacts of review of the work and the health impacts of working in an epidemic/pandemic environment. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:6828.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Public mental health problems during COVID-19 pandemic: A large-scale meta-analysis of the evidence. Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11:384.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Exploring the factors associated with the mental health of frontline healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in Cyprus. PLoS One. 2021;16:eo258475.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A rapid review of the impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of healthcare workers: Implication for supporting psychological well-being. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:104.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Experience of frontline healthcare workers and their views about support during COVID-19 and previous pandemics: A systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21:923.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic's impact on mental health. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2020;35:993-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandemic and mental health of the front-line healthcare workers: A review and implications in the Indian context amidst COVID-19. Gen Psychiatr. 2020;33:e100284.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mental health in COID-19 pandemic: A meta-review of prevalence meta-analyses. Front Psychol. 2021;12:703838.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mental health of frontline healthcare workers exposed to COVID-19 in Egypt: A call for action. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2021;67:522-31.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mental health among healthcare workers and other vulnerable groups during the COVID-19 Pandemic and other coronavirus outbreaks: A rapid systematic review. PLoS One. 2021;16:eo254821.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mental health status among healthcare workers during the covid-19 pandemic. Iran J Psychiatry. 2021;16:250-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The silent pandemic: The psychological burden on frontline healthcare workers during the COVID-19. Psychiatry J 2021:2906785.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The mental health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers, and interventions to help them. A rapid systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 2021;293:113441.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summarizing systematic reviews: Methodological development, conduct and reporting of an umbrella review approach. Int J Evid Based Health. 2015;13:132-40.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of stress, depression, anxiety and sleep disturbances among nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychosom Res. 2021;141:110343.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Investigating the psychological impact of COVID-19 among healthcare workers: A meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:9096.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The psychological impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on health care workers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychol. 2021;12:626547.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of depression, anxiety and stress in China during COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2021;56:210-27.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of depression among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 Outbreak: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Med. 2021;10:3406.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2021;281:91-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of anxiety, depression, burnout syndrome and mental health disorders among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A rapid umbrella review of systematic reviews. J Health Soc Sci. 2021;6:209-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- The impact of SARS-COV-2 on the mental health of healthcare workers in a hospital setting: A systematic review. J Occup Health. 2020;62:e12175.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic in western frontline healthcare professionals: A systematic review. Med Clin (Barc). 2021;156:449-58.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of depression during the COVID-19 outbreak: A meta-analysis of community-based studies. Int J Clin Health Psychol. 2021;21:100196.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Exploring sources of heterogeneity in systematic reviews of diagnostic tests. Stat Med. 2002;21:1525-37.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Global prevalence of mental health issues among the general population during the coronavirus disease-2019 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2021;11:10173.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Factors mediating the psychological well-being of healthcare workers responding to global pandemic: Systematic review. J Health Psychol. 2021;27:1875-1896.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The impact of epidemics and pandemics on the mental health of healthcare workers: A systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:6695.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healthcare worker's burden during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative systematic review. J Multidicipl Healthc. 2021;14:3015-25.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]